On… Money #2

Does it really motivate us?

This is the second of a two part series on the economy, and how our feelings about money can help or hinder our responses to climate change.

This week’s figures showed that the UK has officially entered the deepest recession since records began.

I’m hesitant to post on the economy at such a time, but money is on my mind. It is surely on many peoples’ minds.

Money is the price put on much of what we need, want and value- material or otherwise. So it’s a human construct that each of us participates in creating every single day as we decide what we are willing to pay for what we value.

And, because the economy is a system we are all deeply embedded in, money isn’t just a problem for experts to sort. The way we spend our money is a vote for the type of world we want to see.

The way we spend our money is a vote for the type of world we want to see.

So those of us who feel under-confident to have an opinion about the economy, but who are concerned about the current global direction of travel, might need to step out of our comfort zones with this one.

We might need to own how the wisdom we have gained along our various journeys, much of which may not seem to bear any relation at all, can bring valuable insights to the economic and ecological challenges we are facing.

So this week’s posting is some ideas on how to engage with the economy from a non-economist’s perspective. And to do that, I’ll be looking at money using the lens through which this blog explores most issues; human motivation.

Between a Rock and a Hard Place?

Planetory boundaries means we are fast approaching a glass cieling in terms of economic growth.

Last week’s post on Money drew from Kate Raworth’s excellent book, Doughnut Economics, to question whether infinite material growth is possible on a finite planet, and whether growth of the economy for its own sake can really solve society’s problems.

Climate change means we are fast approaching a glass ceiling on how much of the planet’s resources we can safely use in order to drive the economy, meaning that soon limitless and unchecked material growth will do anything but enhance prosperity.

But in the last quarter the UK’s economy, battered by the pandemic, has shrunk by 20%, leading to a sharp spike in unemployment. And currently we only know of one way out; grow the economy again.

We are between a rock and a hard place. Is there a way forward?

When Something Isn’t Working

The vision of economic growth, first measured as a means of lifting the United States out of the Great Depression, was to bring greater wellbeing to all. It was founded on the belief that each generation could be more prosperous than the previous one, in an infinite continuum of human progress.

Yet the elimination of economic and social inequality still evades us.

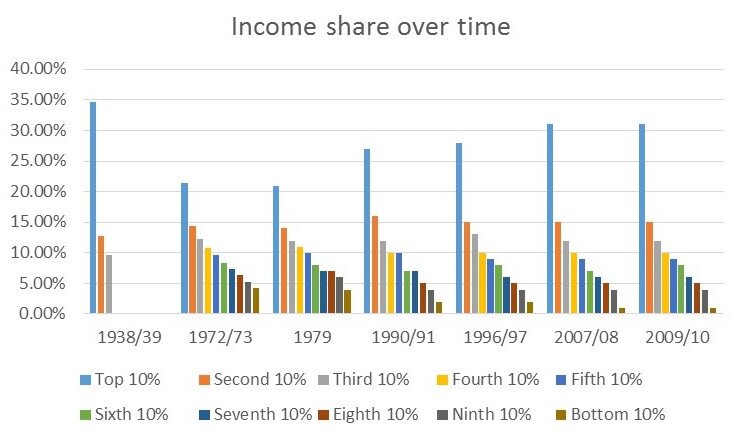

Here in the UK, for example, social inequality actually rose sharply from the 1980s, flatlining in 2010 at levels of inequality not far removed from those before Gross Domestic Product was used to measure economic success.

Image of growing UK inequality taken from www.equalitytrust.org.uk/how-has-inequality-changed

And it is the levels of inequality within a society (rather than levels of wealth) that have shown to be the biggest indicators of obesity, mental ill health, life expectancy, levels of literacy and so on, affecting not just the poor, but the rich also. (I would highly recommend this 15 minute TED talk by the authors of The Spirit Level which explains this brilliant research further).

So, regardless of the climate emergency, perhaps it’s time to start seeking out new solutions because it doesn’t look like economic growth is the most reliable indicator of human wellbeing anyway.

Even the designer of the modern GDP, Simon Kuxnets, said, ‘the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income.’

When We Don’t Already Have The Answers

The difficulty with such an endeavour is that it’s hard to acknowledge something is broken when we don’t know how to fix it. It requires great vulnerability to say, ‘we might need to overhaul the whole system, but we’re not sure how to do it.’

But that’s not to say that there aren’t plenty of good ideas out there.

The Green New Deal, for example, is a growing global movement to invest in sustainable infrastructure and disinvest from fossil fuels. It’s still based on the idea of growth, but puts boundaries around what kind of growth to encourage, and what growth to limit.

It has particularly gained traction in the United States and presents an increasingly clear vision of economic recovery that puts human and planetary flourishing at the heart of the economy.

New Zealand is another example of how to do things differently as last year their Government followed Bhutan in abandoning GDP as a measure of its success in exchange for the Happiness Index which aims to prioritise human wellbeing.

The Gross National Happiness Index is a single number index developed from 33 indicators of citizen’s happiness levels.

Neither of these examples explicitly require a total limitation of economic growth, but they challenge the idea that economic growth is inherently good in and of itself, instead painting a picture of what kind of economic activity is needed in order to optimise prosperity.

They aren’t the full picture, but they are ambitious attempts to take the risk of reaching for something new, even before we are fully sure of what that might look like. They embody creativity, vision, risk taking and the hope of something better.

What Really Motivates Us?

During my time as a professional climate lobbyist, I found it was infinitely more effective to appeal to values such as freedom, pride, integrity or community than it was to talk about money.

If I did make the financial case for climate action to politicians (and there’s a very strong one) it was always in the context of what that money would enable for peoples’ lives. Because, after all, elections are not won on the policies of a party themselves, but on the values those policies embody.

We are actually far less motivated by money than we might think we are.

In her third chapter Raworth lists a wide range of instances that challenge our understanding of how humans relate to money.

Studies consistently show that we’re willing to give up financial gains for other values such as being part of a community.

For example, ten nurseries tried to reduce the number of parents dropping their children off late by introducing a small penalty. The result? The number of late arrivals significantly increased because parents saw the fine as payment for the late arrival, thus feeling that it nulled the wrong.

Raworth also cited research showing that far more blood is donated in the UK- given voluntarily- than in the US where people are paid for their contribution.

Similarly, a study in Tanzania found that those who were offered a small payment for spending half a day planting trees together were 20% less likely to participate than those that weren’t. Why? Because fostering a sense of community was a far stronger motivation than the small financial gain.

Keeping Up With the Jones’

Research shows that we’re not motivated by money, we’re motivated by people. The inequality researchers and authors of The Spirit Level, mentioned above, write;

“Strengthening community life is hampered by the difficulty of breaking the ice between people, but greater inequality amplifies the impression that some people are worth so much more than others, making us all more anxious about how we are seen and judged.”

Essentially inequality is especially damaging because it creates a sense of some people being worth less than others.

It affects our sense of self, which is exactly why consumerism is so alluring.

We live in a world where what we own determines much of how we are seen by others, and how we are seen by those whose opinions we care about means a great deal to us.

The Need to Belong

I have a strong childhood memory of stepping into a clothes shop on my own for the very first time.

Much of my life I had worn clothes made for me by my Mum and grandparents. I look back now and wish I could make some of those beautiful outfits for myself, but as a child I quite often felt self conscious about how I looked. It didn’t help that I had struggled to make friends and fit in at school anyway.

So at fourteen years old I remember entering that clothes shop and staring at the limitless supply of gorgeous fabrics modelled by the kinds of girls I had always wanted to be like. For a certain price I learned I could buy something that could transform the way the world saw me. That I could perhaps even buy social acceptance.

I was hooked, not on buying nice clothes, but on the feeling that those clothes gave me and what they compensated for.

The Rise of the Consumer

Material possessions cannot compensate for immaterial gaps in our lives, like a sense of community, or hope.

That’s the moment that I began to see myself as a consumer. I began to believe that if I worked hard enough and earned enough money it was possible to buy what I felt I lacked in myself.

It’s a part of my identity that I still wrestle to rid myself off now.

We all do, in our different ways, because that’s how we taught to see ourselves.

And the term ‘consumer’ is now routinely used in place of ‘citizen’ and ‘people’. You will see this language used just as much in the world of politics as you will see it used in the world of businesses.

This is a dangerous shift because the language we use about ourselves matters enormously.

A study at Northwestern University has shown, for example that when presented with a hypothetical water shortage scenario, those who the test referred to as ‘consumers’ were significantly more selfish than those who were referred to as ‘citizens’. According to the study, there were no other variables;

‘The “consumers” rated themselves as less trusting of others to conserve water, less personally responsible and less in partnership with the others in dealing with the crisis. The consumer status, the authors concluded, “did not unite; it divided.”’

What Are We Here For?

The problem with infinite economic growth is that it requires consumers in order to keep the system going.

But humans are so, so much more than just consumers placed on this earth to acquire wealth as if this is the only helpful thing we can really do for society.

We are creators, explorers, lovers, survivors, trailblazers, liberators, carers, healers and so, so much more than that. What brings our life meaning is the experiences we have, the people we share the journey with and what we discover along the way.

There is an increasing tendency for politicians to refer to citizens as consumers, but we are so, so much more than what we contribute to the economy or what we consume.

As I have found my people in the world, the ones who accept me as I really am, the grip that clothes buying used to have on me has loosened.

So I’ll finish with three suggestions to help shake up the economy if you’re a non-economist.

Become a conscious consumer- In the book, Thanks, which I recommend in my Eco-Anxiety series, Robert A.Emmons encourages us to think of ourselves as ‘mindful materialists’. I find this a really helpful way of thinking about my relationship to what I consume. It’s not bad to enjoy material things, but it’s no good if we can’t savour them or if we’re using them to compensate for something else in life.

Think of yourself as a regenerator- Look for opportunities to create and restore the material world as an antidote to consuming. It might be that you grow your own herbs or plant a small pot of veg. It might be that you mend something you would otherwise have thrown away. Perhaps you craft your gifts this year. And be watchful of when you hear the word consumer being used in the place of citizen!

Write to your MP- Inspire your MP to do the unthinkable and begin questioning whether we couldn’t do better with our economic model. Point them in the direction of New Zealand’s recent endeavours and you might even want to send them a copy of Kate Raworth’s book. You can also contact Hope for the Future if you want help in drafting a letter to your MP.

If you’re interested in finding out more about ‘awakening to a new economics’ you may want to have a look at the Joy In Enough campaign, which has all sorts of ideas and resources suitable for everyone.

About Me

I’m Jo, formerly the founder Director of national climate change charity, Hope for the Future. I am currently researching eco-anxiety and how we can build emotional resilience in our response to the climate emergency.

Welcome to Climate.Emergence- a place to emotionally process what on earth is happening to us and our planet.